Embodiment Abstracted: The Influence of Yvonne Rainer

Curated by Elise Archias

Gallery 400

January 13-March 4, 2017

Artists

Yvonne Rainer | Natalie Bookchin | Gregg Bordowitz | Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker | Ralph Lemon | Simon Leung | Meg Stuart

quote Heading link

That’s why 250,000 people marched and chanted in downtown Chicago last Saturday, alongside millions more around the world. The aesthetic and historical framework offered by “Embodiment Abstracted” couldn’t be more timely.

| Critic for the Chicago Tribune

For an Art of Bodies in History Heading link

“No to spectacle,” Yvonne Rainer wrote more than fifty years ago, and we will say it again today.1 But the artworks in this exhibition suggest the list that follows that initial negation in Rainer’s format, might look something like this now:

No to spectacle,

to stylish formulations of the new,

to cool fugitivity and escapes into defensive vagueness,

to macho staring into the abyss of social death,

to retraumatizing the audience,

to manic proliferation of signs that mimic a day of clicking,

to dwarfing sublimity, to entropic spinning out into clouds of particles, to networks that think mere extension is enough.

Yes to bodies in history,

to relationships that take work,

to making sure the audience feels something that they will want to put into words,

to the poetic labor of an old body that has encountered new tasks before,

to living with disease, and together demanding better care, to significant gestures, to breaking them down until they are less and then more significant,

to making them signify differently with a different physicality and psyche,

to taking control of one’s own distortion,

to the reinterpretation of old stories, to the repurposing of old spaces,

to the formation of a collective voice built of particular suffering and particular desire,

to artists who want us to understand what has allowed them to flourish in this unjust world.

—Elise Archias

- What has come to be known as Rainer’s “No Manifesto” is a paragraph on page 178 of the following text: Yvonne Rainer, “Some retrospective notes on a dance for 10 people and 12 mattresses called ‘Parts of Some Sextets,’ performed at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, Connecticut, and the Judson Memorial Church, New York, in March, 1965,” The Drama Review, vol. 10, no. 2 (Winter 1965): 168-178.

Yvonne Rainer, Spiraling Down (2008) & Assisted Living: Good Sports (2011) Heading link

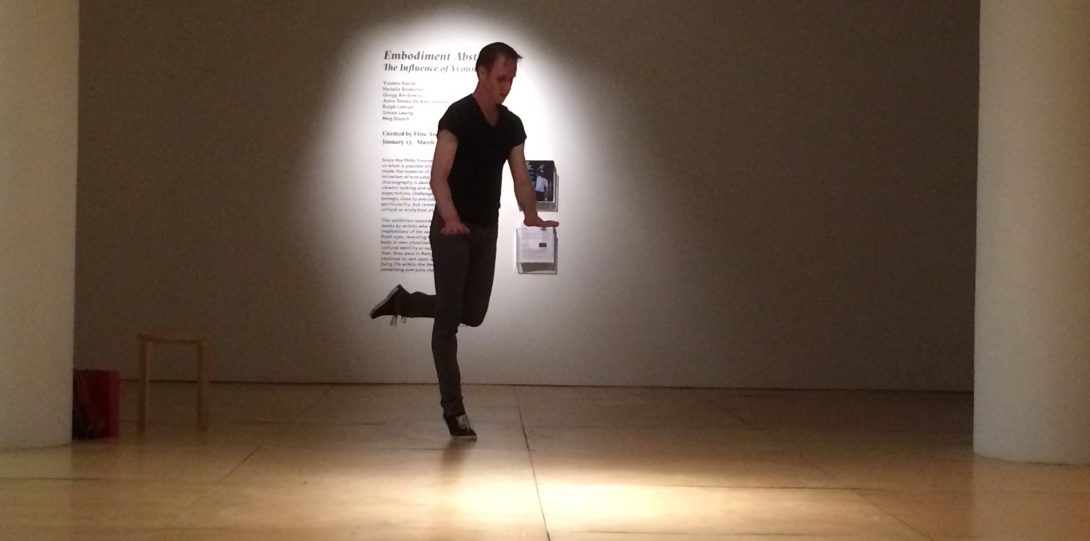

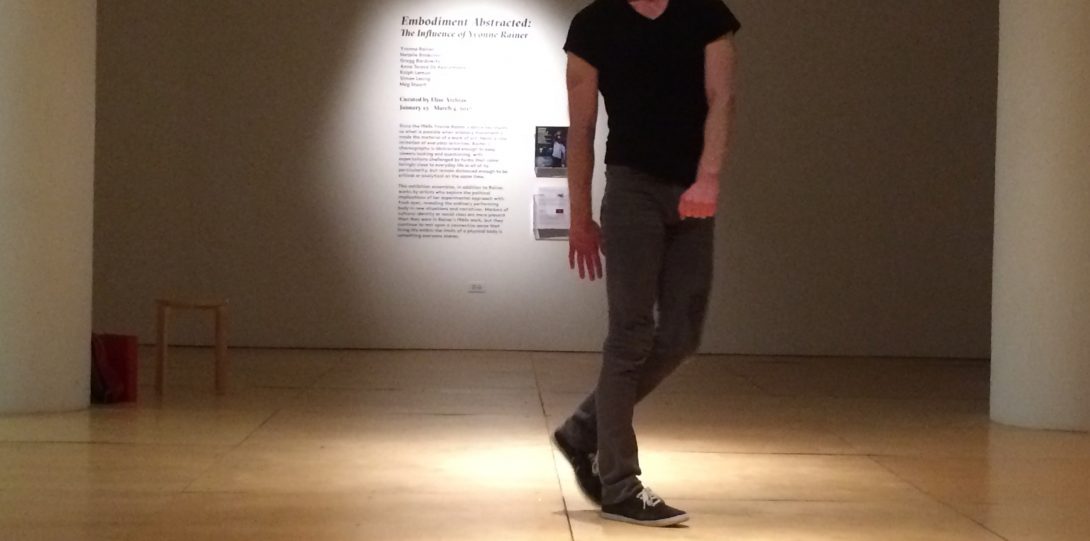

Excerpts from dance pieces Spiraling Down, 2008, and Assisted Living: Good Sports, 2011, choreographed by Yvonne Rainer, 2015 Merce Cunningham Awardee, Foundation for Contemporary Arts.

About the exhibition Heading link

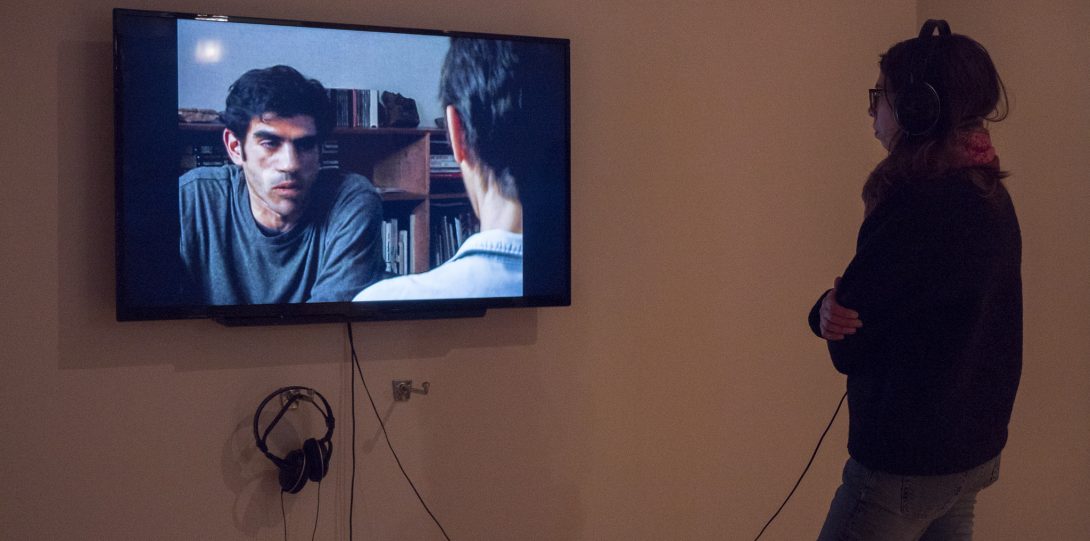

Since the 1960s Yvonne Rainer’s dance has shown us what is possible when ordinary movement is made the material of a work of art. Never a rote imitation of everyday activities, Rainer’s choreography is abstracted enough to keep viewers looking and questioning, their expectations challenged by forms that come lovingly close to everyday life in all of its particularity, but remain distanced enough to be critical or analytical at the same time. Embodiment Abstracted: The Influence of Yvonne Rainer gathers together works made by contemporary artists who take up Rainer’s experimental approach to the body in performance and explore its political implications with fresh eyes. These artists influenced by Rainer—Ralph Lemon, Jimmy Robert, Gregg Bordowitz, Simon Leung, Natalie Bookchin, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Meg Stuart—create situations or tell stories in which the specific ways bodies perform tasks, give in to gravity, or simply take up the needs and challenges that their daily lives entail are central to what the viewer identifies and empathizes with. Markers of cultural identity or difference are present, but accommodated by a connective sense that living life within the limits of a physical body is something everyone shares.

Consisting of ten works of video, film, videotaped performance, and live performance—including a new work by Yvonne Rainer—Embodiment Abstracted moves the ordinary performing body central to Rainer’s approach in the 1960s into new territory. The exhibiting artists expand Rainer’s vision of everyday life to include new categories, such as aging bodies, tasks in a rural setting, layers of literary history embedded in urban spaces, the voices of people living in poverty, the AIDS crisis in the U.S. and South Africa, Shakespeare-sized passions expressed without language, the body’s manic distortions, and its smallest inherited gestures. These newer works diversify Rainer’s generalized, predominately white bodies of the 1960s with performers of different races and who explicitly emphasize gender, sexuality, social class, or chronic illness. At the same time, the younger artists hold firm to her refusal to give the body that appears in the work over entirely to its identity categories or geographic particulars.

The artists in the exhibition were for the most part born in the 1960s and came of age at postmodernism’s high point. For many in the 1980s and 1990s, postmodernism meant shuffling available signs to demonstrate enough fluency in a language of surfaces and systems to deconstruct that language. By contrast, for the artists in the exhibition, the appropriation of cultural references is always tied to the embodied experience of need, pleasure, or suffering in history. The resulting works are more analytical than deconstructive, oriented toward how living and meaning go forward within constraining conditions and limited representational systems. The art of this century has yet to be fully written into art history, but Embodiment Abstracted suggests it might one day be remembered as a time when artists made figurative artworks that combined particular social categories and general, connective forms in order to express earnest and wide-reaching political aspirations.