Members of the Department Preview Their CAA Talks, Part 2: EMMANUEL ORTEGA and NICOLETTA ROUSSEVA

UIC Art History Colloquium

January 31, 2020

3:30 PM - 5:00 PM

Emmanuel Ortega (Visiting Assistant Professor)

“The Mexican Picturesque: Nineteenth-Century Sentimentality and the Visual Construction of the Nation”

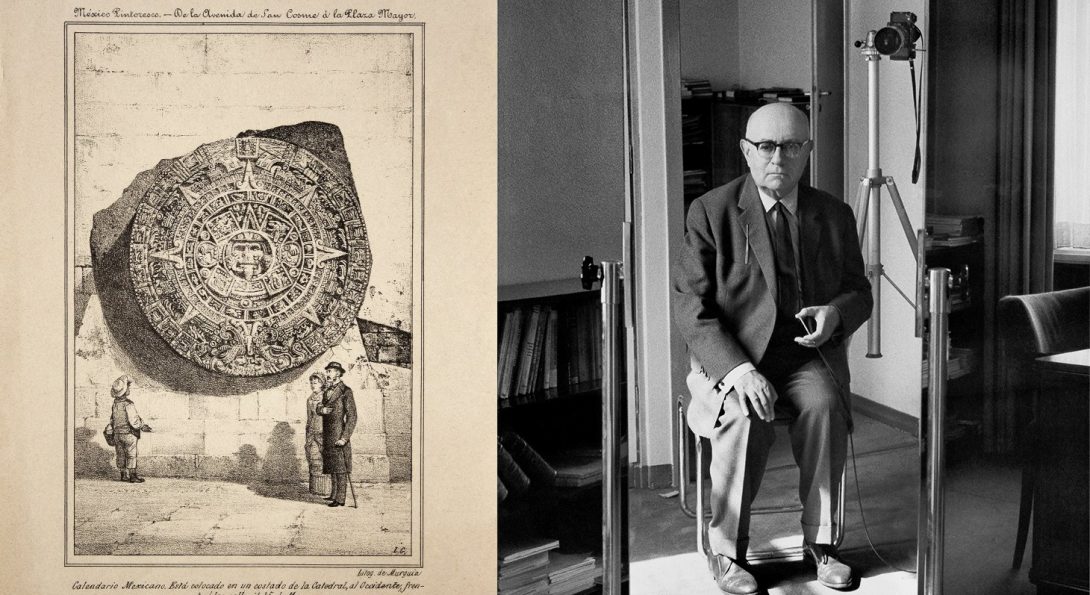

In this presentation, I will explore the function of the picturesque in Mexico during the late nineteenth-century. Picturesque landscapes, through their seemingly innocent charm, create a superficial diversion, which veils their political function. In 1880, for instance, an image titled “Calendario Mexicano” by Luis Garcés appeared in Mexico Pintoresco Artistico y Monumental. The lithograph depicts an indigenous boy contemplating the Aztec Calendar, while a fashionable city couple observes the boy. In this context, Garcés constructs several “encounters”— ethnic, regional and temporal. These three factors activate each other in a triangular composition; the presence of indigeneity is signified by a child who perceives the grandeur of the Aztec past, while the hope of a civilized future is embodied by the beholding couple; a false unity of nationhood.

A few years later, El ahuehuete de la noche triste (1885) by José María Velasco depicts an encounter between an indigenous spectator and the ahuehuete, a grand tree, which according to sixteenth-century conquest chronicles, witnessed the tears of Hernán Cortés after his army’s defeat in 1520. His composition transforms the violence of the conquest into a placid encounter between native and historic monument, revealing the function of the picturesque in Mexico; to hide the murderous encounters of empire and amplify sentiments of the nation.

Indigenous contemplation becomes the activating agent in the Mexican picturesque. In both images, Garcés and Velasco, respectively, have captured a perfectly sentimentalist moment where time stands still, and the grandeur of the historic monuments, promoted sentiments of national pride in their viewers. By understanding the picturesque as a byproduct of sentimentality, we can easily recognize images of nation building celebrating a sanitized history, and ultimately the justification of modernity by appealing to human emotions.

Nicoletta Rousseva (PhD Candidate)

“Adorno after Socialism”

As Eastern Europe’s socialist regimes crumbled and pundits heralded history’s end, Fredric Jameson recommended none other than “Adorno as a dialectical model for the 1990s.” Testing Jameson’s assertion, this paper considers whether Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory can offer a critical framework that accounts for the complexities of art in the years after socialism and in our troubled neoliberal epoch. To this end, I examine why certain artists in Eastern Europe, particularly, in former Yugoslavia, continued to affirm state socialism’s attitudes, social structures, and artistic traditions even after its political model failed. I ask how Adorno’s posthumous work, so concerned with art’s guilt and culpability, can help elucidate the broader significance of this distinctive artistic response. Rather than valorizing the outworn role of the artist as dissident always in opposition to state power, what value is there in the work of artists who make themselves answerable to history’s most transformative forces? What critical and political trajectories might such an approach make viable today?

Date posted

Jan 21, 2020

Date updated

Jan 24, 2020